Context

default trust scores and the inheritance of influence down the context tree

One of the central functions of the Grapevine is to calculate how much influence, i.e. how much credibility, to attribute to any given entity in any given context. The influence score is needed so that the Grapevine can properly sift through a sea of attestations by all sorts of users on all sorts of topics. This allows you to rely upon other entities to help you in many ways: to establish the technical details underlying digital communications; to select content such as a social media feed; to make recommendations such as a movie to watch; or to answer questions such as what is happening in the world.

In a previous post, we reviewed the basics of the Grapevine algorithm for calculating Influence. We made the case that it does a much better job than legacy social media of finding the high value users and high value content that would otherwise be hidden by the distractions of social media “influencers” [1] and their high follower counts. In this article we focus on the contextual nature of trust attestations, of the influence score, and of the myriad of other scores (like average product ratings) that are used to select content, answer questions, etc.

In particular, we will review the process of inheritance of influence score down the context tree from generic to specific and argue this is one of the essential features that will convert web of trust from a pipe dream into a system that actually works.

Multidimensional representation of context

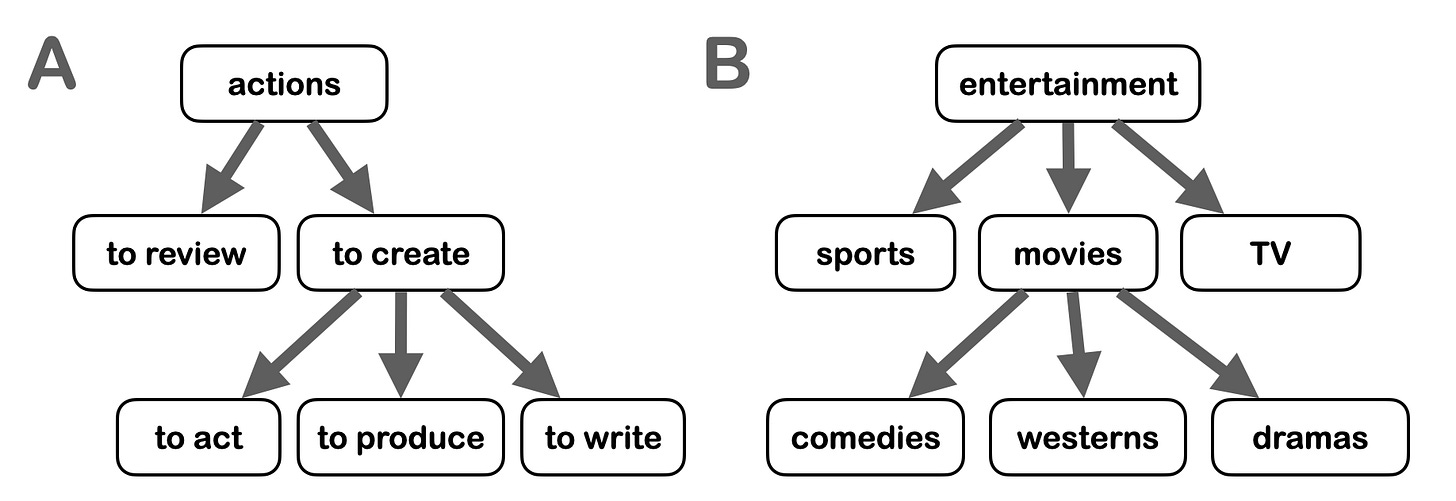

We are going to use two dimensions to represent a context: the actions dimension (Figure 1A) and the categories dimension (Figure 1B). Using these two dimensions, Alice can provide independent attestations of her belief regarding Bob’s abilities to review (action) movies (category), to produce sci-fi movies, to act in westerns, or to write romantic comedies, just to name a few examples.

Each of these dimensions will be organized into a hierarchy, as in the example of Figure 1 which shows a hierarchy of actions (Figure 1A) and a hierarchy of categories (Figure 1B). Each of these hierarchies will be curated by the Grapevine using the DCoG protocol.

This two dimensional method may or may not be the best way to represent a context. Would three dimensions be better? Or maybe the use of multiple dimensions is too much complication? In the long run, it doesn’t matter, because your Grapevine will have the ability to curate a list of methods and will help you decide which method is the best one for any given purpose. Our two dimensional system doesn’t need to be perfect; it needs only to be good enough to get things off the ground.

Uses

Context has multiple uses, including:

trust ratings, e.g. Alice trusts Bob to recommend movies

influence scores, e.g. Alice’s Grapevine tells her that Bob is good at recommending movies

categorization of content, e.g. Bob’s rating of the Godfather as the best movie of all time is a movie recommendation

By making reference to the same context (using the same pair of universal unique identifiers for the recommend action and the movies category) we can ensure that Alice’s rating impacts Bob’s influence score, which in turn impacts the list of movie recommendations as seen by any user whose Grapevine connects to Alice and Bob.

Evolution of context over time

The fact that the graphs of categories and actions are managed by the Grapevine using the DCoG protocol means that they will evolve over time. Items (nodes in the graph) can be expected to be added, removed, and rearranged in real time. No matter how detailed a graph may be, there will always be the possibility of fleshing portions of it out in ever greater detail. As discussed below, out algorithms will need to take this fact into account.

inheritance from parent to child

The algorithms for calculation of influence are designed so that the default score for a child context, such as producing westerns, is determined by a parent context, such as making movies. We refer to this feature as inheritance of trust.

The inheritance of trust is essential to the basic utility of the Grapevine. If Alice wants to know Bob’s expertise in some particular context, she will want her Grapevine to synthesize together and reap the benefits from all the relevant attestations available to her: the ones making reference to broad, general categories as well as those making reference to narrow, specific categories. Consider the fact that information in the form of trust attestations referencing a broad category like literature is almost always going to be more readily available than that referencing a narrow category like 16th century French long prose fiction. If attestations in some generic context is all she’s got, that’s what she will use. But if more specific information is available, that should be taken into account, and should override the broad information. This is the primary purpose of the system of inheritance.

The notion that specific information should “override” inherited generic information takes advantage of the certainty variable that we discussed earlier. Recall that attestations include a confidence — e.g., Alice thinks Bob might be as smart as Einstein, but this was based on only a brief interaction so she’s only 5% confident — and that average trust score and influence scores are associated with a certainty. Each of these components is a number between 0% and 100%. Let’s imagine that Alice owns a radio station and wants to hire a commentator for a show on field hockey. She gets 100 applicants, too many for her to interview them all, and uses her Grapevine to help her decide which ones to invite for an interview. Based on directed attestations, her Grapevine considers Bob to be highly skilled at commentary on sports in general, with an 80% certainty. Unfortunately, in the context of commentary on field hockey, the Grapevine indicates a poor performance. But her Grapevine is only 10% certain of this because it is based on scant information. Using the method of inheritance, the Grapevine algorithm synthesizes these numbers together into a composite estimate of his skill as a commentator in field hockey. Without going too much into the details of the equations, the calculations are designed to mirror the way we would synthesize such information in real life. Alice’s Grapevine is highly confident that Bob is highly skilled at sports commentary in general; but in the absence of more specific information, how certain can Alice be of his skill in the niche category of field hockey? She would probably want the algorithm to drop that 80% certainty down a bit. And she may want to manually input how much that drop should be. Cut it in half? Multiply it by one-fourth? To accomplish this, one or more additional user-adjustable attenuation factors, specific for inheritance, will likely be introduced into the algorithm.

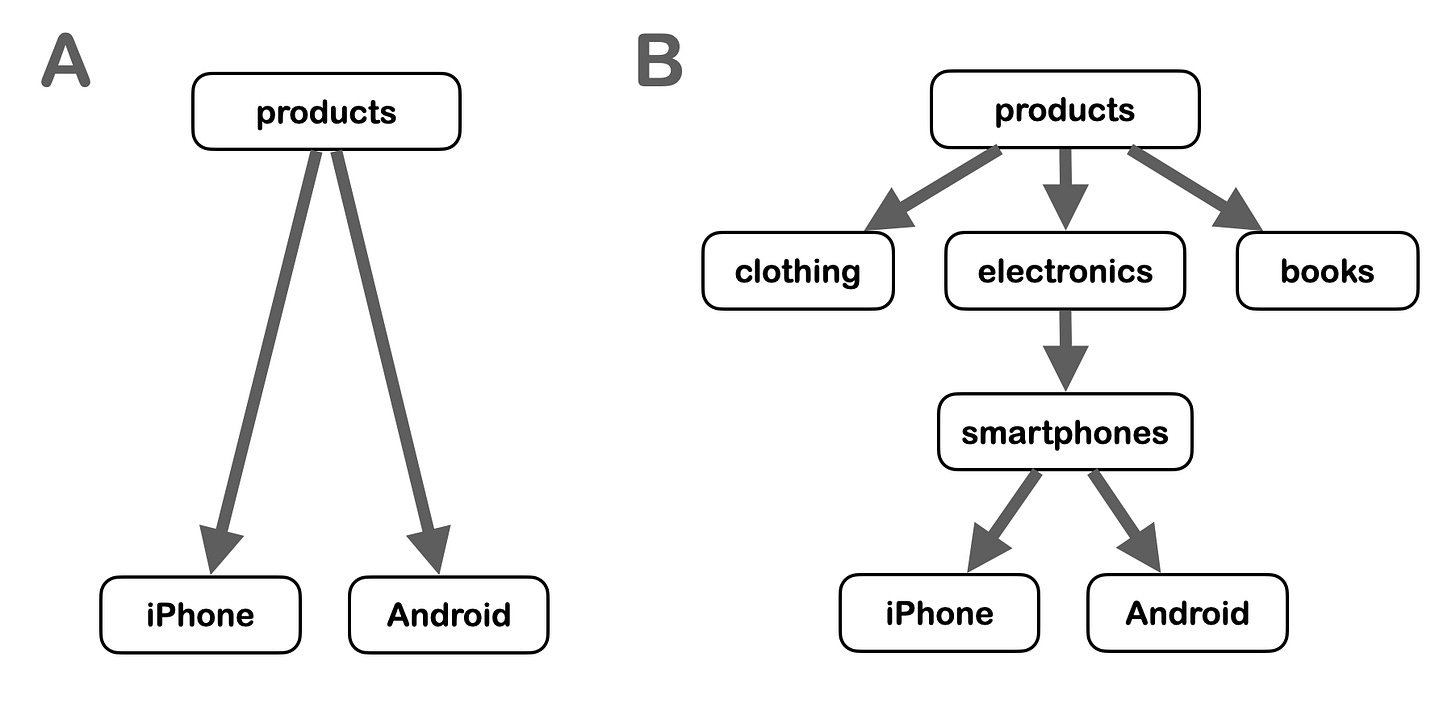

One might be tempted to apply the inheritance attenuation factor for each step down the context tree. However, it is important for the influence score algorithms to be created in a fashion so that the act of adding detail to the context trees must not, in and of itself, alter the resulting trust scores. For example: using the graph of Figure 2A, the default trust score for Bob in the context of rating iPhones is inherited from his trust score for rating products. Suppose now that the Grapevine adds detail to the graph by adding two new nodes: electronics and smartphones, along with edits to the relevant relationships as in Figure 2B. We do not want editing of this nature to have any impact on Bob’s trust score for rating iPhones. Of course, this will change if someone in the web of trust were to create a new attestation regarding Bob’s ability to rate smartphones or electronics. The way to accomplish this goal is the following: by default, the attenuation down the context tree is set to 1, i.e. multiply the score by 1 so there is no attentuation. But Alice’s control panel will give her the option of manually introducing an attenuation from parent context to child context — e.g. an attenuation factor of 0.8 from products to iPhone (Figure 1) — and this will not be screwed up by the interim addition of additional nodes in the context tree, as occurs between Figure 1A and 1B.

summary

A “context” refers to a specific action and a specific category.

Actions and categories are organized into hierarchical directed acyclic graphs (DAGs), which we may refer to as hierarchies or “context trees.”

The curation of these graphs is delegated to the Grapevine.

These hierarchies are used to establish default trust scores, with default trust scores “inherited” from parent to child.

Trust score inheritance enables the Grapevine to synthesize generic data with specific data in a fashion that takes into account the relative certainties in these pieces of data, similar to the way we would synthesize such estimates in real life.

We want the context trees to be useful regardless of whether they are sparsely populated with few details or densely populated with lots of detail.

Inheritance calculations must be performed so that influence scores are not altered by changes in the resolution of the context trees.

The Pretty Good teck stack will be rolled out in stages: DCoSL, DCoG, and trust score inheritance. How will users react? We anticipate: DCoSL will be a noteworthy, but maybe not more than a curiosity. Nostr devs will care, but not the average nostr user. The addition of DCoG will provide genuine utility: the average nostr users will want to use it. It will probably not be until the introduction of inheritance that we will enable content curation so powerful that it will attract the attention of users beyond nostr enthusiasts.

notes

[1] The term social medial “influencer” is not to be confused with the Grapevine’s notion of influence. They are not the same thing!